Curatorial Exhibit Proposal

Printed Dreams: Edo Woodblocks to Modern Manga explores the evolution of ukiyo-e—Japan’s vibrant woodblock prints—and their parallel with contemporary manga. By reframing how we understand Edo-period visual culture, the exhibition highlights the deep historical roots of a medium that now shapes global storytelling. This project brings fresh relevance to traditional printmaking while offering audiences a bridge between past and present Japanese art.

The Floating World Reimagined

Before our world of phones, tablets, and endless scrolling, there was another kind of visual universe—a place called the ukiyo, or “floating world.” In the cities of Edo-period Japan, artists carved and printed scenes of daily life, famous actors, elegant courtesans, lively festivals, and dramatic landscapes. These prints, called ukiyo-e, were the entertainment, fashion magazines, movie posters, and comics of their time.

Yet they were more than pictures. They were windows into how people lived, dreamed, and saw themselves.

Ukiyo-e artists watched the world closely. They studied how people moved, how clothes folded, how waves curled, how light touched a face. Their lines were quick and full of life, capturing a moment before it slipped away. Even their materials had stories: natural dyes that faded softly over time, later joined by new bright pigments like Prussian blue from the West. Every print required teamwork—an artist to design it, a skilled carver to shape the woodblocks, and a printer to bring the image to life with color.

As the floating world changed, so did the art. Landscapes stretched wider. Waves grew taller and more dramatic, showing both beauty and fear during a time when Japan felt the growing presence of other nations. Scenes of the pleasure districts—private, glamorous, and sometimes erotic—revealed the real social and cultural world of Edo, not just its fantasies. Behind each print was a mix of artistry, humor, performance, and everyday truth.

Modern manga grows out of this same spirit.

Manga, like ukiyo-e, uses bold lines, strong characters, and fast storytelling. It shows daily life, but also adventure, emotion, and imagination. It uses simple shapes to express big feelings. And just like woodblock prints, manga is made to be shared, enjoyed, and passed from person to person.

This exhibition follows that long connection—from woodblocks to comic panels, from Edo streets to today’s bookstores and screens. It shows how artists then and now try to capture life as it really feels: sudden, expressive, funny, dramatic, and always moving. The floating world never disappeared—it simply changed form.

Printed Dreams invites you to slow down and look closely. Notice the lines, the gestures, the colors. Feel how the past speaks to the present. Let yourself drift between centuries and see how images, no matter how they are made, carry stories that continue to shape us.

Featured Artworks

-

After Toba Sōjō (Kakuyū) (1053–1140)

Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga / 鳥獣人物戯画 [Scrolls of Frolicking Animals and Humans]Reproduction published by JAPAN MUSEUM SEIUM, 21st century, after 12th-13th c. Heian-Kamakura period original

Ink on paper handscroll (emakimono)

32 × 1180 cm (12.6 × 465 in)Gregory Allicar Museum of Art, 2025, Museum purchase.

Often celebrated as Japan’s earliest example of comic art, Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga animates a world where frogs wrestle, rabbits pray, and monkeys officiate in parody of human ritual. Created in a time of strict religious hierarchy, its playful satire gently subverts the solemnity of court and temple life through humor and motion rather than text. The brushwork—spontaneous, calligraphic, and unbroken—moves the viewer’s eye from right to left in a continuous visual rhythm that anticipates the sequential storytelling of later ukiyo-e and, ultimately, modern manga.

This scroll marks a crucial point in Japan’s visual lineage: from sacred ink painting to the popular woodblock prints of Edo, and onward to the cinematic frames of contemporary manga and anime. Its spirit of empathy and satire—depicting animals as mirrors of human behavior—echoes across centuries of Japanese visual culture, reminding us that even laughter and line can carry profound cultural memory.

-

After Utagawa Toyokuni I (Japan, 1769–1825)

Untitled (Group of Three Courtesans with Young Apprentices, at Shrine)

Early 20th century reproductionColor woodcut on paper

15 5/16 x 10 3/16 inchesGregory Allicar Museum of Art, CSU, gift of George and Alice Drake, 1989.1.16

In Edo, prints of courtesans sold because they delivered access.

Affordable and portable, they let merchants and artisans—rich in cash, poor in status—step into the chic theater of the pleasure quarters. Hairpins, layered kimono, house crests, even a shrine outing like this one: every detail reads like a style guide and a city map. Publishers knew it. They watched trends, commissioned series, and refreshed faces with the seasons, turning bijin-ga [pictures of beautiful women] into a steady market—part fashion plate, part fan culture, part advertisement.This impression reproduces Toyokuni’s signature and the Utagawa School brand forward into the 1900s, when celebrated Edo designs were recut and reprinted for new audiences. What you hold, then, is both glamour and afterglow: a modern echo of the “floating world” and the everyday desire that kept it in print.

Description text goes here

-

After Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Different Views of Men, from Hokusai Manga, Vol. 4, p. 4 (left)

Reproduction circa 20th centuryColor woodcut on paper

7 3/4 x 5 1/8 inchesGregory Allicar Museum of Art, CSU, gift of George and Alice Drake, 1989.1.12

In this lively page from Hokusai's Manga volume 4, the artist captures the humor, motion, and diversity of human character. Warriors, laborers, nobles, and even a horned demon come to life through swift, economical brush lines—an exercise in observation that feels spontaneous yet deeply empathetic.

Published in 1816, Hokusai's Manga series was a visual encyclopedia of Edo life, blending instruction, entertainment, and satire. As Yoshiaki Shimizu notes, such works embody the spirit of ukiyo—the “floating world” that celebrated everyday experience and impermanence.

Hokusai’s sketchbook became a prototype for modern Japanese comics: sequential imagery, caricature, and expressive gesture converge to tell human stories without words. These “whimsical pictures” bridge centuries, showing how the playful linework of Edo woodblocks evolved into the dynamic visual language of today’s manga.

Description text goes here

-

After Kitazawa Rakuten (北澤 楽天, 1876–1955)

Tokyo Puck

2025 reproduction of 1909 magazine coverReproduction on canvas

13 × 9 inches

Gregory Allicar Museum of Art, 2025, Museum purchase.

Japan’s first professional cartoonist, Kitazawa Rakuten, transformed the art of satire into a modern visual language. As founder and chief artist of Tokyo Puck—

a bilingual humor magazine published from 1905 to 1912—Rakuten blended Western caricature with Japanese sensibility, creating an entirely new form of social commentary. Printed in bold color lithography, the February 1909 cover reflects the optimism and anxiety of Japan’s Meiji-era modernization, when steamships, top hats, and new technologies collided with traditional customs.Rakuten’s distinctive linework and expressive humor evolved from the spirit of ukiyo-e—the “pictures of the floating world”—but his use of sequential imagery and exaggerated expression anticipated the visual style of contemporary manga and anime. Both playful and political, Tokyo Puck offered its readers laughter as a means of reflection, documenting how Japan imagined itself in a globalizing world. Today, Rakuten’s work stands as a cornerstone in the visual history connecting Edo-period woodblock prints to modern graphic storytelling.

-

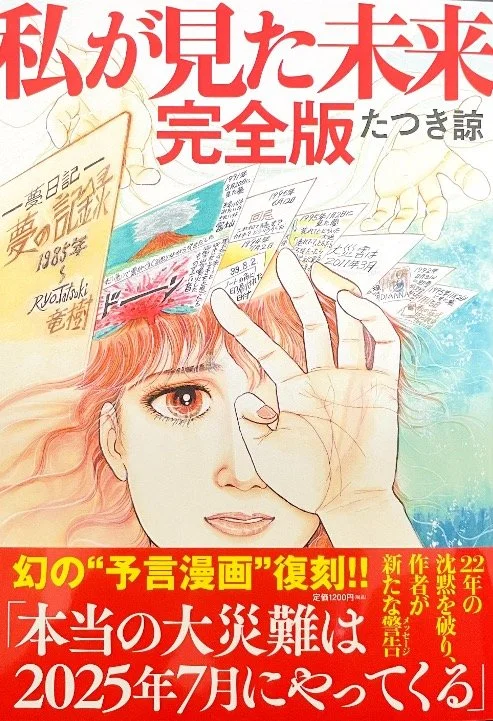

Ryō Tatsuki (b. 1954)

Watashi ga mita mirai/私が見た未来 [The Future I Saw]

1999; reissued 2021Printed manga volume; ink on paper

18 × 13 cm (book)Private collection of Tiffany Hajicek

When manga artist Ryō Tatsuki began sketching scenes from her dreams, she wasn’t chasing prophecy—she was trying to understand the strange language of the unconscious. Published in 1999, The Future I Saw gathered these dreams into quiet vignettes about impermanence and fate, drawn with the tender, emotional linework of shōjo manga.

A single date on its cover—“March 2011: Great Disaster”—turned this private meditation into public myth. After the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, readers saw in Tatsuki’s dreams an eerie echo of reality. The manga was reprinted in 2021, when she revealed another dream foretelling a July 2025 catastrophe.

What began as a personal record became a mirror for a nation’s collective unease. As the story spread online, travel plans shifted, headlines flared, and officials reminded citizens that earthquakes cannot be predicted. Yet the work endures not because it foretells disaster, but because it names the human feeling underneath it—our wish to glimpse the future, and our fear of what it might reveal.

Exhibit Collection Overview

The remaining twenty or more artworks in this exhibition present a collection of prints and manga that support the exhibit’s narrative. It spans multiple eras: Edo period ukiyo-e, Meiji, and early twentieth century shin hanga and modern manga. Together they demonstrate the continuity of Japanese storytelling. This range shows how artists consistently used line, gesture, atmosphere, and sequential thinking to communicate emotion, humor, and cultural identity. By including canonical artists—Hokusai, Hiroshige, Utamaro—and modern creators such as Rakuten and Tatsuki we illustrate the lineage that reaches from pre-modern print culture into today’s manga ecosystem.

Ultimately, Printed Dreams is an anchored exhibit that offers visitors an encounter with physical artworks to ground the historical to the modern narrative in authentic objects that embody Japan’s long relationship with printed art. The specific pieces themselves are curated to echo themes of impermanence, beauty, satire, travel, celebrity, domestic life, and imagination. This reminds us that visual storytelling has always been woven into Japanese life.